The term 'polycentricity' is widely abused to suggest a uniform repeating tessellation, which ignores the hierarchy of centers. People accept the hierarchy of C-store, strip mall, mall, but get uncomfortable with the fact that the hierarchy also implies the emergence of a regional uber-mall. Likewise, downtowns get uncomfortable that the fact that any sufficiently large downtown will see the emergence of regional office sub-centers. Place hierarchy is an emergent property of the trade-offs between transportation costs and rents.

Showing posts with label urban economics. Show all posts

Showing posts with label urban economics. Show all posts

Wednesday, July 16, 2025

Wednesday, October 24, 2018

Is urban water distribution a natural monopoly?

Arguably, for water, it's a natural monopoly. Public streets typically provide easements for both water and sewer. Both leak, especially with age. So there is a clear need to separate them, so cities put water lines on one side, and sewer lines on the other. Water lines have to be buried below the local frost line, so a second set would need to be even deeper, and provide structural support for the first set previously provided by undisturbed soil. The same is true of sewer, which must be low enough to drain into.

Friday, June 30, 2017

Streetcar vs. Automobile in 1917

Free roads and free parking subsidize the automobile. Why not transit?

"Because it benefits so few people--only 3% of people take transit to work".

And how many people took automobiles to work in 1917*?

"..."

That's right. Because we have no idea.

MODE ACCESS

We know that about 30% owned cars. (No idea how many had access to transit--have to find that out someday)

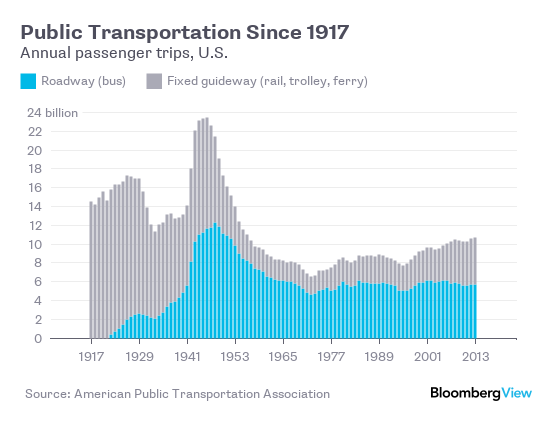

Compare that to the number of people who were riding transit at that time:

TRIPS MADE

In 1917, there were 14 Billion transit riders, so about 131 transit trips for every person in the United States. Sadly, no data for auto users, so we still can't make an apples-to-apples comparison.

MILEAGE DRIVEN

We have some estimate of how many automobile miles were driven: About 30 billion. Or, for a U.S. population of 106.5 million, about 289 miles a year. With 260 working days in a year, that is about a mile a day.

Data for transit is proving difficult to find, and even APTA doesn't have it for before the 1970's. The best they've got is vehicle miles**: In 1920, there were 1,922 million vehicle miles (1,922,000,000)..but that's just how far the trolleys traveled, not how far the people on board them traveled. Without knowing how many people were on board, we can't compare person-mileage.

*Streetcars reached their apex in 1917, the same year Federal funding of roads started. Whether the Feds just switched to what would have been the winning horse anyway is difficult to know.

** I'm leaving out subways and commuter railways so there can be no "that's just New York" whining.

"Because it benefits so few people--only 3% of people take transit to work".

And how many people took automobiles to work in 1917*?

"..."

That's right. Because we have no idea.

MODE ACCESS

We know that about 30% owned cars. (No idea how many had access to transit--have to find that out someday)

Compare that to the number of people who were riding transit at that time:

TRIPS MADE

In 1917, there were 14 Billion transit riders, so about 131 transit trips for every person in the United States. Sadly, no data for auto users, so we still can't make an apples-to-apples comparison.

MILEAGE DRIVEN

We have some estimate of how many automobile miles were driven: About 30 billion. Or, for a U.S. population of 106.5 million, about 289 miles a year. With 260 working days in a year, that is about a mile a day.

Data for transit is proving difficult to find, and even APTA doesn't have it for before the 1970's. The best they've got is vehicle miles**: In 1920, there were 1,922 million vehicle miles (1,922,000,000)..but that's just how far the trolleys traveled, not how far the people on board them traveled. Without knowing how many people were on board, we can't compare person-mileage.

*Streetcars reached their apex in 1917, the same year Federal funding of roads started. Whether the Feds just switched to what would have been the winning horse anyway is difficult to know.

Urban Phase Shift?

One of the comments on this article was so great I had to repost it:

In pre-industrial (and third world slums) the only access available is by walking, and so some truly hideous densities result.

It's theoretically feasible that a city might stop growing***. But most cities don't--instead, they invest in transportation improvements. NYC built it's first subways in the name of "De-Congestion".

One of the ideas I'm kicking round is an urban scaling induced 'phase shift' in the effectiveness of transportation improvements. Namely, total metro population drives average metropolitan density. (As you get bigger, you naturally get denser). At small sizes and low densities, auto-mobility works: Land is cheap, parking is available, walking anywhere is madness. And it keeps working, as long as your addition of automobile capacity keeps up with congestion.

However, while travel is an 'derived demand' in terms of the number of trips made, it's a 'induced demand' in terms of the length of trips made. If you make traveling cheap and easy, people go further.* Urban form is 'set' by the dominant transportation mode at the time of construction**. So places developed under conditions of auto-mobility tend to be low-density with segregated land-uses. The large amount of travel required to get around for basic needs is 'baked-in' at that point.

from: https://people.hofstra.edu/geotrans/eng/ch6en/conc6en/cellular_automata.html

As the number of zones increases, the average distance from one zone to another also increases. Which means, all else equal, the amount of travel required to get to all the places you want to go also rises. Simply because things are scattered about: home in one place, work in another, groceries in a third, kids-school in a fourth, soccer in another, ballet-practice in another, dentist in yet another.

The big problem is that the increase in average distance between all of these things is non-linear. Every additional 'zone' you add to a city, the average distance rises more than it did for the last zone.

Even if the road lane miles per capita (and associated costs) remain constant, the amount of travel doesn't. As travel demand outstrips supply, congestion results.

Some cities try to fix this increasing congestion with massive increases in road-building. Failure is inevitable. Exponential increases in travel require exponential increases in road capacity, imposing exponential costs on a linearly growing population.

And so at some point, every city gets the 'rapid transit bug'. And it has to be rapid transit, because only rapid transit makes it possible to avoid congestion. Non-rapid transit, such as regular buses and streetcars, are undeniably cheaper to build than rapid transit (sometimes by an order of magnitude).

But that doesn't matter. Rapid transit is premium transit*****. It's transit for choice riders (people who could drive, but choose not to). And to get people to make that choice, it has to be better (in some way) that the driving alternative.

Non-rapid transit suffers from congestion. It's less convenient, less reliable, and less comfortable than your personal automobile. You don't have a 'locker' to store things in, and hauling groceries is difficult. Thus, it can almost never compete with a private automobile (excepting when parking costs/hassles are enormous).****

Rapid transit is better than the personal automobile when it is a) faster, b) cheaper, and c) more reliable. 'a' only happens when congestion is fierce; transit vehicles make repeated stops. 'b' seems simple, but for most people a car is a 'stock' of mobility they can draw upon even with no money, while transit is a 'pay-per-use' thing, so it seems expensive, even if it is less expensive in aggregate. Again, 'c' is reliant on congestion to work.

In summary: Auto-mobility works until it doesn't. It stops working because average travel distances increase exponentially as the metro area expands, while population increases linearly. This makes it impossible to keep expanding roadway capacity to match demand. (Some try; all fail). As travel demand outstrips supply, congestion results.

The total amount of delay drivers experience is exponentially proportional to the amount of congestion (from: https://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/congestion_report/chapter2.htm) The AADT/C ratio is the ratio of traffic to capacity.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

***This may be one of the reasons for competing cities, closer together. When a city reaches maximum walkable density, it makes a great deal of sense to go elsewhere. Of course, large cities have huge advantages in terms of access to resources and agglomeration economies, which (typically) more than offset the cost of congestion. I expect the only time you'd really see such a switch is for 'Twin cities' like Minneapolis-St. Paul, or the Texas MetroPlex.

*The reverse is also true. As congestion increases, trip length should start falling.

**The trouble being that urban form is fixed at date of construction, and is very difficult to retrofit for alternative transportation modes. Adding highways to NYC came at enormous financial and social cots. Retrofitting auto-dependent cities will likely be painful/costly as well.

****Which is why buses to downtowns, Universities and hospitals work--they are all places with terrible parking.

*****The political quid-pro-quo of rapid transit for dependent riders is that "Hey, you too can ride the premium transit!". The flip side to that is that the high cost of rapid transit means less of it is provided--its goes fewer places. Typically, bus operations get cut to pay for capital improvements, which leaves the transit-dependent population worse off.

When I took my Urban Economics course from Barton Smith, one of the observations Smith told us in class was that whenever prices for major goods and services in an urbanized area keep going up (and housing is certainly a big part of most people's budgets), eventually prices will reach a point where they will become a market signal to everyone that the urbanized area needs to stop growing. Population growth will either come to a halt, or people will start leaving until prices fall to an equilibrium where people can afford to live there again. - Neil MeyerI think it gets to the core of why city promoters like transportation improvements--without affordable housing, cities can't grow. Affordable housing includes both rents and access costs. As rents in one area rise, people can offset that by moving to nearby areas with lower rents (and higher access costs).

In pre-industrial (and third world slums) the only access available is by walking, and so some truly hideous densities result.

It's theoretically feasible that a city might stop growing***. But most cities don't--instead, they invest in transportation improvements. NYC built it's first subways in the name of "De-Congestion".

One of the ideas I'm kicking round is an urban scaling induced 'phase shift' in the effectiveness of transportation improvements. Namely, total metro population drives average metropolitan density. (As you get bigger, you naturally get denser). At small sizes and low densities, auto-mobility works: Land is cheap, parking is available, walking anywhere is madness. And it keeps working, as long as your addition of automobile capacity keeps up with congestion.

However, while travel is an 'derived demand' in terms of the number of trips made, it's a 'induced demand' in terms of the length of trips made. If you make traveling cheap and easy, people go further.* Urban form is 'set' by the dominant transportation mode at the time of construction**. So places developed under conditions of auto-mobility tend to be low-density with segregated land-uses. The large amount of travel required to get around for basic needs is 'baked-in' at that point.

This is problematic, if the metropolitan area keeps expanding.

from: https://people.hofstra.edu/geotrans/eng/ch6en/conc6en/cellular_automata.html

As the number of zones increases, the average distance from one zone to another also increases. Which means, all else equal, the amount of travel required to get to all the places you want to go also rises. Simply because things are scattered about: home in one place, work in another, groceries in a third, kids-school in a fourth, soccer in another, ballet-practice in another, dentist in yet another.

The big problem is that the increase in average distance between all of these things is non-linear. Every additional 'zone' you add to a city, the average distance rises more than it did for the last zone.

Even if the road lane miles per capita (and associated costs) remain constant, the amount of travel doesn't. As travel demand outstrips supply, congestion results.

Some cities try to fix this increasing congestion with massive increases in road-building. Failure is inevitable. Exponential increases in travel require exponential increases in road capacity, imposing exponential costs on a linearly growing population.

And so at some point, every city gets the 'rapid transit bug'. And it has to be rapid transit, because only rapid transit makes it possible to avoid congestion. Non-rapid transit, such as regular buses and streetcars, are undeniably cheaper to build than rapid transit (sometimes by an order of magnitude).

But that doesn't matter. Rapid transit is premium transit*****. It's transit for choice riders (people who could drive, but choose not to). And to get people to make that choice, it has to be better (in some way) that the driving alternative.

Non-rapid transit suffers from congestion. It's less convenient, less reliable, and less comfortable than your personal automobile. You don't have a 'locker' to store things in, and hauling groceries is difficult. Thus, it can almost never compete with a private automobile (excepting when parking costs/hassles are enormous).****

Rapid transit is better than the personal automobile when it is a) faster, b) cheaper, and c) more reliable. 'a' only happens when congestion is fierce; transit vehicles make repeated stops. 'b' seems simple, but for most people a car is a 'stock' of mobility they can draw upon even with no money, while transit is a 'pay-per-use' thing, so it seems expensive, even if it is less expensive in aggregate. Again, 'c' is reliant on congestion to work.

In summary: Auto-mobility works until it doesn't. It stops working because average travel distances increase exponentially as the metro area expands, while population increases linearly. This makes it impossible to keep expanding roadway capacity to match demand. (Some try; all fail). As travel demand outstrips supply, congestion results.

The total amount of delay drivers experience is exponentially proportional to the amount of congestion (from: https://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/congestion_report/chapter2.htm) The AADT/C ratio is the ratio of traffic to capacity.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

***This may be one of the reasons for competing cities, closer together. When a city reaches maximum walkable density, it makes a great deal of sense to go elsewhere. Of course, large cities have huge advantages in terms of access to resources and agglomeration economies, which (typically) more than offset the cost of congestion. I expect the only time you'd really see such a switch is for 'Twin cities' like Minneapolis-St. Paul, or the Texas MetroPlex.

*The reverse is also true. As congestion increases, trip length should start falling.

**The trouble being that urban form is fixed at date of construction, and is very difficult to retrofit for alternative transportation modes. Adding highways to NYC came at enormous financial and social cots. Retrofitting auto-dependent cities will likely be painful/costly as well.

*****The political quid-pro-quo of rapid transit for dependent riders is that "Hey, you too can ride the premium transit!". The flip side to that is that the high cost of rapid transit means less of it is provided--its goes fewer places. Typically, bus operations get cut to pay for capital improvements, which leaves the transit-dependent population worse off.

Friday, June 23, 2017

Public Policy always implies subsidy--either to someone, or to their competitors.

Reading Peter Gordon's blog always reminds me that all public policies imply subsidies--either to someone, or to someone's competitors.

When they began, our health and safety regulations are a 'subsidy' for companies already engaging in them. The Dodd-Frank Act on banking is often decried as a subsidy for big banks, because the cost per customer of compliance is lower than for smaller banks.

My friend Rob refers to me as a 'Parking Republican' as I have zero issue with pricing either parking or roads. And why not? It's fiscally sound and economically efficient. Von Thunen pointed out that there is always direct trade-off between rents (real estate) and transportation costs, and the whole field of urban economics is based on it. As a nation, we invested piles of money in lowering transportation costs (adding roads). This massively lower the cost of transportation, which then massively lowered the cost of urban land. (Hence turning central cities into slums for a fifty years).

Free roads and free parking subsidize the automobile. Why not transit?

When they began, our health and safety regulations are a 'subsidy' for companies already engaging in them. The Dodd-Frank Act on banking is often decried as a subsidy for big banks, because the cost per customer of compliance is lower than for smaller banks.

My friend Rob refers to me as a 'Parking Republican' as I have zero issue with pricing either parking or roads. And why not? It's fiscally sound and economically efficient. Von Thunen pointed out that there is always direct trade-off between rents (real estate) and transportation costs, and the whole field of urban economics is based on it. As a nation, we invested piles of money in lowering transportation costs (adding roads). This massively lower the cost of transportation, which then massively lowered the cost of urban land. (Hence turning central cities into slums for a fifty years).

Free roads and free parking subsidize the automobile. Why not transit?

Wednesday, June 1, 2011

Peak VMT?

The Melbourne Urbanist has a pretty great graphic:

The post discusses 'peak travel', the idea that the industrialized world has hit a peak, and gross Vehicle Miles Traveled (VMT) will never be as high as they were in mid-2007. Gas prices are frequently mooted as the cause, which seems plausible.

But what struck me was less then decline in per capita miles traveled then the decline in Per Capita GPD. Historically, there has been a strong correlation between vehicle miles driven and economic growth, but the exact causal relationship has always been fuzzy--do richer countries drive more, or is more driving required for greater economic activity? (The latter is a favorite argument of the road lobby).

But gas prices are high, additional credit constrained, and American consumers are broke. I theorize that the price of gas has disrupted the American economic engine in unanticipated ways. It's not just businesses that are suffering from high gas prices, but employees. The Journey to Work is typically the farthest Americans travel in a week, and thus the one that uses the most gas. When gas was cheap, it made sense to live far from your job, where housing was cheap. The time-cost was high, but time is cheaper than gas.

With the housing market frozen, moving is much more difficult, so 'home' is fixed, and workers have to choose from jobs that are close enough that they can afford to drive there. And thus we have lingering long-term employment.

But what struck me was less then decline in per capita miles traveled then the decline in Per Capita GPD. Historically, there has been a strong correlation between vehicle miles driven and economic growth, but the exact causal relationship has always been fuzzy--do richer countries drive more, or is more driving required for greater economic activity? (The latter is a favorite argument of the road lobby).

But gas prices are high, additional credit constrained, and American consumers are broke. I theorize that the price of gas has disrupted the American economic engine in unanticipated ways. It's not just businesses that are suffering from high gas prices, but employees. The Journey to Work is typically the farthest Americans travel in a week, and thus the one that uses the most gas. When gas was cheap, it made sense to live far from your job, where housing was cheap. The time-cost was high, but time is cheaper than gas.

With the housing market frozen, moving is much more difficult, so 'home' is fixed, and workers have to choose from jobs that are close enough that they can afford to drive there. And thus we have lingering long-term employment.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)