Is it ok for SLC to be selfish? To prefer projects which benefits it's citizens, in preference to in-commuters?

Certainly, there are out-commuters--Census on the Map suggests about 50k of them (vs 200k in-commuters). But they probably don't care--they are making a reverse-commuter, out-commuting on roadway facilities sized for going-home traffic, so experienced roadway congestion is likely minor.

Read an article today, nothing that the people in central city Chicago didn't benefit from freeways, that the freeways actually made walking commuters longer, and drastically reduced the number of long-distance trips residents took. The argument was made that the total welfare gain from freeways is probably overstated--it ascribes all sorts of benefits to freeways, but failed to account for their costs (disproportionately suffered by central city dwellers).

Secondly, conversed with a co-worker, in which I described freeways as 'walls', and as 'pollution and noise spewing black holes'. So for a SLC resident, for voters and the representatives they elect...should they care about suburban in-commuters, who are merely using the city streets as neighborhoods as highways? Clearly not, so it falls to the business community to make the case for access, for being accessible to places, for access to customers and employees as important to the economy of the city, and to lobby for it.

The logical conclusion of the business community prioritizing in-commuters is something like Houston--a central city purely for in-commuters, and vacant after dark. The urban nadir. That model has been followed, its limits found. You can read the retrospective when city plans start talking about building 'night-time cities'. Creating entertainment venues downtown, working on street festivals, holding gallery strolls. Next phase being building a '24-hour city', with residents--people living and working within the city. Perhaps the next tier up is what is now being called the '30 minute city', where all the things you need are within a 30 minute trip (by bike and walk).

Asking how far things in NYC, my brother replied "About half an hour

away" (by subway). Places that weren't barely existed. We know that trip

frequency decays exponentially with increase in distance (ie, if 20

minute trips are common, 10 minute trips are 4x as common, and 30 minute

trips half as common).

Omaha, Nebraska...now confronting the 'Urban Transportation Problem' of exponentially rising traffic congestion (as increasing urban size generates increasing average travel distances), and could feel it's comfortable existence as a 15-minute city collapsing--everything was no longer within an easy 15 minute drive.

The 15-minute city is a good way to live. Urbanism is the realization that the good life can no longer be achieved by increasing automobility, and that other modes are required. Transit only works when it's Fast, Frequent, and Reliable (as Seattle's frequent network) has shown.

Previously, I've speculated that SLC needs it's own transit authority. It has a lot of transit, but it's a whole lot of routes that are 'half-in' SLC--seeming to serve SLC, but recall that there are 4-more in-commuters than out-commuters, so the half-in/half-out routes actually serves SLC citizens less than the shear split of route/service mileage might suggest--they are making more 'internal' trips within SLC, and might prefer the service to be so distributed.

SLC has got the the 'nightime' city down, but not quite the 24-hour city. To be a 24-hour city, SLC would need to better balance it's population and employment. Research by Dr. Reid Ewing suggests the empirically appropriate ratio to be 2 jobs for every 5 persons. SLC's current population ~200k, and employment about 661k. Five-halves that would be 1.2m...so SLC would need to add a million people, which is rather unlikely, but however provides an interesting intuition into the rest of the Wasatch Front - there are 2 million people on it, and half of them work in Salt Lake City. And on the taxes on their place of employment SLC depends.

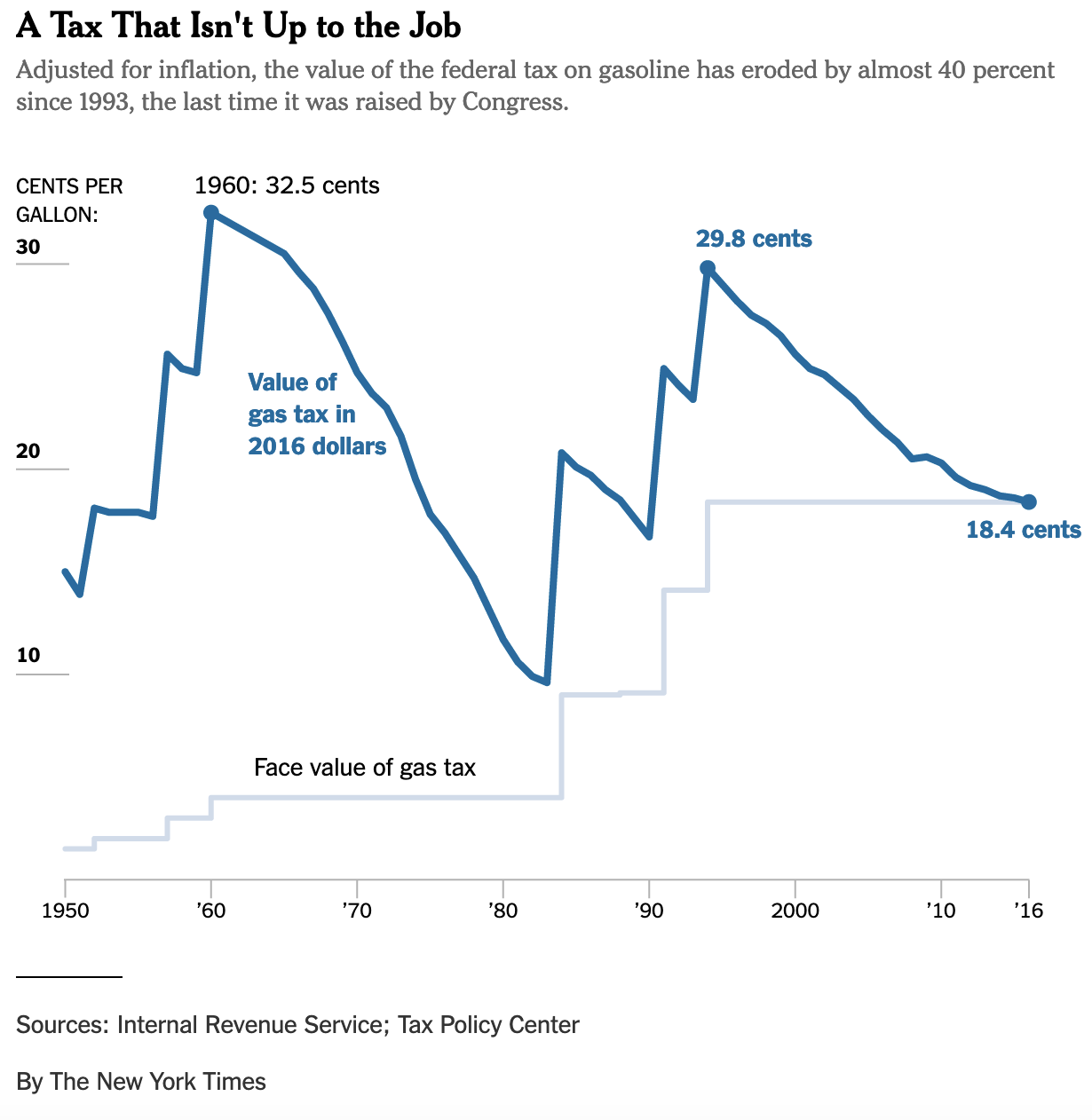

The reality is probably worse: The inputs to making roads (asphalt) were likely subject to higher than average inflation--asphalt and gasoline both come from oil, and refiners got cleverer about

The reality is probably worse: The inputs to making roads (asphalt) were likely subject to higher than average inflation--asphalt and gasoline both come from oil, and refiners got cleverer about