One of the comments on

this article was so great I had to repost it:

When I took my Urban Economics course from Barton Smith, one of the observations Smith told us in class was that whenever prices for major goods and services in an urbanized area keep going up (and housing is certainly a big part of most people's budgets), eventually prices will reach a point where they will become a market signal to everyone that the urbanized area needs to stop growing. Population growth will either come to a halt, or people will start leaving until prices fall to an equilibrium where people can afford to live there again. - Neil Meyer

I think it gets to the core of why city promoters like transportation improvements--without affordable housing, cities can't grow. Affordable housing includes both rents and access costs. As rents in one area rise, people can offset that by moving to nearby areas with lower rents (and higher access costs).

In pre-industrial (and third world slums) the only access available is by walking, and so some truly hideous densities result.

It's theoretically feasible that a city might stop growing***. But most cities don't--instead, they invest in transportation improvements. NYC built it's first subways in the name of "De-Congestion".

One of the ideas I'm kicking round is an urban scaling induced 'phase shift' in the effectiveness of transportation improvements. Namely, total metro population drives average metropolitan density. (As you get bigger, you naturally get denser). At small sizes and low densities, auto-mobility works: Land is cheap, parking is available, walking anywhere is madness. And it keeps working, as long as your addition of automobile capacity keeps up with congestion.

However, while travel is an 'derived demand' in terms of the number of trips made, it's a 'induced demand' in terms of the length of trips made. If you make traveling cheap and easy, people go further.* Urban form is 'set' by the dominant transportation mode at the time of construction**. So places developed under conditions of auto-mobility tend to be low-density with segregated land-uses. The large amount of travel required to get around for basic needs is 'baked-in' at that point.

This is problematic, if the metropolitan area keeps expanding.

from: https://people.hofstra.edu/geotrans/eng/ch6en/conc6en/cellular_automata.html

As the number of zones increases, the average distance from one zone to another also increases. Which means, all else equal, the amount of travel required to get to all the places you want to go also rises. Simply because things are scattered about: home in one place, work in another, groceries in a third, kids-school in a fourth, soccer in another, ballet-practice in another, dentist in yet another.

The big problem is that the increase in average distance between all of these things is non-linear. Every additional 'zone' you add to a city, the average distance rises more than it did for the last zone.

Even if the road lane miles per capita (and associated costs) remain constant, the amount of travel doesn't. As travel demand outstrips supply, congestion results.

Some cities try to fix this increasing congestion with massive increases in road-building. Failure is inevitable. Exponential increases in travel require exponential increases in road capacity, imposing exponential costs on a linearly growing population.

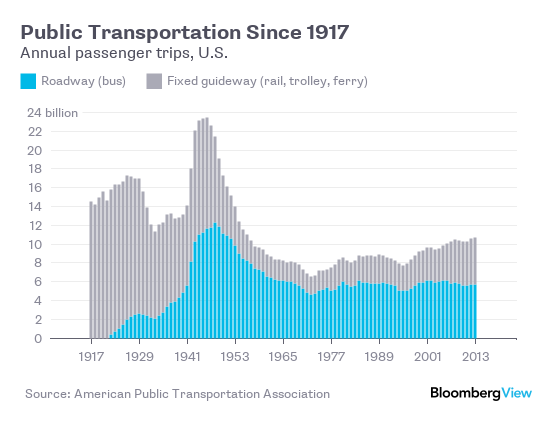

And so at some point, every city gets the 'rapid transit bug'. And it has to be rapid transit, because only rapid transit makes it possible to avoid congestion. Non-rapid transit, such as regular buses and streetcars, are undeniably cheaper to build than rapid transit (sometimes by an order of magnitude).

But that doesn't matter. Rapid transit is premium transit*****. It's transit for choice riders (people who could drive, but choose not to). And to get people to make that choice, it has to be better (in some way) that the driving alternative.

Non-rapid transit suffers from congestion. It's less convenient, less reliable, and less comfortable than your personal automobile. You don't have a 'locker' to store things in, and hauling groceries is difficult. Thus, it can almost never compete with a private automobile (excepting when parking costs/hassles are enormous).****

Rapid transit is better than the personal automobile when it is a) faster, b) cheaper, and c) more reliable. 'a' only happens when congestion is fierce; transit vehicles make repeated stops. 'b' seems simple, but for most people a car is a 'stock' of mobility they can draw upon even with no money, while transit is a 'pay-per-use' thing, so it seems expensive, even if it is less expensive in aggregate. Again, 'c' is reliant on congestion to work.

In summary: Auto-mobility works until it doesn't. It stops working because average travel distances increase exponentially as the metro area expands, while population increases linearly. This makes it impossible to keep expanding roadway capacity to match demand. (Some try; all fail). As travel demand outstrips supply, congestion results.

The total amount of delay drivers experience is exponentially proportional to the amount of congestion (from: https://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/congestion_report/chapter2.htm) The AADT/C ratio is the ratio of traffic to capacity.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

***This may be one of the reasons for competing cities, closer together. When a city reaches maximum walkable density, it makes a great deal of sense to go elsewhere. Of course, large cities have huge advantages in terms of access to resources and agglomeration economies, which (typically) more than offset the cost of congestion. I expect the only time you'd really see such a switch is for 'Twin cities' like Minneapolis-St. Paul, or the Texas MetroPlex.

*The reverse is also true. As congestion increases, trip length should start falling.

**The trouble being that urban form is fixed at date of construction, and is very difficult to retrofit for alternative transportation modes. Adding highways to NYC came at enormous financial and social cots. Retrofitting auto-dependent cities will likely be painful/costly as well.

****Which is why buses to downtowns, Universities and hospitals work--they are all places with terrible parking.

*****The political quid-pro-quo of rapid transit for dependent riders is that "Hey, you too can ride the premium transit!". The flip side to that is that the high cost of rapid transit means less of it is provided--its goes fewer places. Typically, bus operations get cut to pay for capital improvements, which leaves the transit-dependent population worse off.